Deeksha Tyagi

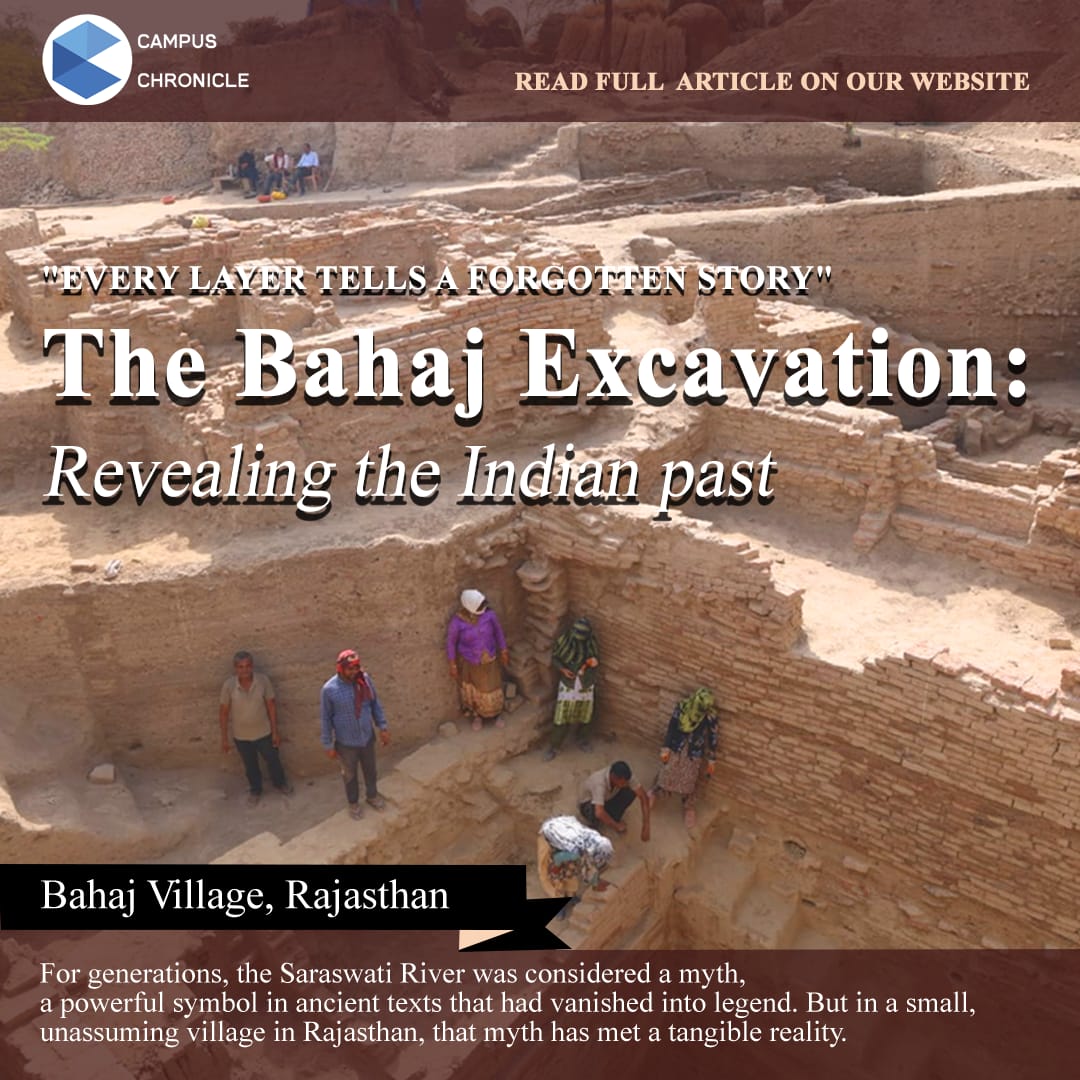

Bahaj is the kind of place you would miss if you blinked on the Bharatpur-Mathura road: a dusty knoll, a cluster of buff houses, and fields now pocked with neat squares of excavation spoil. Yet 23 metres beneath that nondescript mound lies a palaeo-channel that has torn a four-millennia hole in our received chronology and thrown the politics of India’s early history back into the public square. The Archaeological Survey of India’s trench—already the deepest ever dug in Rajasthan—has exposed an ancient dried-up riverbed whose sediments hold carbonised seeds, microliths and hearth ash datable between 3500 and 1000 BCE. Some researchers think the channel’s course tracks the long-debated Saraswati; others counsel caution and more geochemical work. Either way, the very existence of such an old watercourse in the Braj uplands is a finding that will force hydrologists, geomorphologists and historians to redraw the hydrographic map of north-west India. For traditionalists that time-window instantly evokes the Saraswati described in the Rig Veda; for sceptics it is a stratigraphic puzzle that must be solved grain by grain. The ASI, to its credit, has refused to pronounce a verdict, filing an interim report that calls the channel “hydro-civilisationally significant” yet stops short of naming names.

Artefact density at Bahaj is astonishing. Stratified floors yield ochre-coloured pottery in the lowest layers, painted grey ware in the middle, and fine red ware in the upper reaches, signalling occupation from late Harappan through Mahājanapada to the Gupta horizon and beyond that. Copper and silver punch-marked coins surface beside tiny clay sealing-stamps impressed with early Brahmi letters; if those letters are authenticated in situ they will nudge the birth of the Indian syllabary back by as much as four centuries, making Bahaj as disruptive for epigraphy as Keeladi has been for Tamil Brahmi.

House-pits framed with earthen posts, furnaces lined with vitrified clay, and a defensive earthen wall show a community confident in both metallurgy and urban craft specialisation. Bead-makers working carnelian, shell bangle turners, and bone-tool smiths shared space with agrarian households storing grain in globular jars. Terracotta icons of Śiva-Pārvatī and fifteen neatly plastered yajña-kuṇḍas ringed with miniature pots suggest a ritual sphere already leaning toward Śākta practice by the first millennium BCE. A single, flexed-burial skeleton dispatched to an Israeli lab for aDNA and isotopic analysis may yet situate Bahaj in wider Bronze-Age mobility networks.

Methodology matters as much as the objects. Even more striking is the social archaeology. Earlier digs in Rajasthan often fenced villagers out; here the team spent months talking in schools, mollifying rumour-mongers, and inviting local farmers to watch sorting tables. That ethic of negotiation may prove as durable a legacy as the antiquities themselves.

Why does any of this matter beyond Deeg? First, the site compresses four thousand years of cultural layers into a single trench less than 50 km from Mathura, a city whose early chronology has long been hobbled by poor stratigraphy. Bahaj gives that chronology a clean, datable backbone and will ripple into Buddhist, Śunga and Kushan studies. Second, if the palaeo-channel can be chemically tied to Ghaggar-Hakra sediments farther west, the Saraswati debate—derided by some as nationalist myth-making—will at last have a testable dataset instead of arm-waving. Such a result would embolden right-of-centre historians who have argued for an indigenous river-valley civilisational continuum and will oblige sceptics to address evidence rather than ideology. Third, those four sealings with Brahmi letters are not an epigraphic side-show: they threaten the consensus that puts the script’s emergence under Mauryan statecraft. A pre-Mauryan Brahmi pushes organised literacy, record-keeping and perhaps even early Prakrit literature into the so-called “dark” centuries—a change that will ripple through textbook narratives from primary school to UPSC syllabi.

Unsurprisingly, the trenches have already become a proxy battlefield. Central ministers have tweeted the dig as proof of Vedic historicity, while critics warn of “saffron archaeology” bent on reading scripture into stratigraphy.

The dig’s greatest potential may be intellectual, not political. A settlement that begins in late Harappan horizons and ends in Gupta-period debris offers a living laboratory to study how Vedic, Śramanic, Śaiva and Vaiṣṇava currents inter-penetrated rural society; how copper yields to iron without economic collapse; how script uptake changes bureaucratic practice; how water systems shift when a river goes underground. Every metre down the trench is an invitation to rewrite one more generalisation in our textbooks.

Caution, however, is archaeology’s first commandment. The Saraswati link will remain speculative until optically-stimulated luminescence dates, rare-earth element ratios and remote-sensing align along the entire channel path. The Brahmi sealings require palaeographic peer review and thermoluminescence cross-checks. Radiocarbon assays must be published raw, not as press-release bullet points. Only then will Bahaj move from media sensation to peer-reviewed baseline. In that sense the site is a test of India’s capacity to let science breathe amid heated identity politics. If we fail, the trench will be just another slogan pit. If we succeed, Bahaj could stand alongside Rakhigarhi, Dholavira and Keezhadi as a cornerstone of a truly pan-Indian ancient history—one that is empirical, plural and compelling even to those who do not share the nationalist imagination.

It deserves our attention not because it flatters any political camp, but because it proves—again—that the past beneath our feet is richer, older and more complex than any slogan. The challenge is to let that complexity speak before we bury it under the next round of headlines.